PARTICIPATORY URBANISM & YOUR DESIGN PRACTICE

nb: this post was originally published on December 5, 2015.

WHAT DOES PARTICIPATORY URBANISM MEAN FOR YOUR DESIGN PRACTICE?

A few years ago I published this piece in MONU (Magazine ON Urbanism) about geographic urbanism as a form of participatory theater between places and the people that live in those places. I was recently corresponding with Bernd Upmeyer, editor-in-chief of MONU, and he thought I might be interested in their current issue on Participatory Urbanism. He was right. It’s all about participatory design practices and it got me thinking about what participatory urbanism means for my consulting practice and I wanted to reflect a bit on how the ideas of participatory urbanism presented in MONU #23 help designers deal with ambiguity, authenticity, and the temporality that comes with continually shifting user populations.

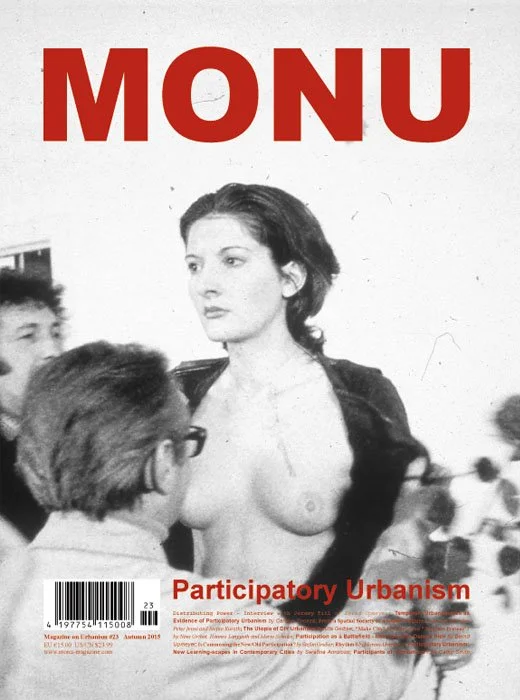

(MONU #23 Cover Image: Rhythm 0, performance, from Marina Abramovic’s contribution on page 82. Location: Studio Morra Naples, 1974, Photo: Donatelli Sbarra. ©Marina Abramovic. Image is courtesy of the Marina Abramovic Archives), used with permission of the publisher.

PARTICIPATORY URBANISM WANTS YOU TO GIVE UP CONTROL

MONU #23 opens with Distributing Power, an interview with Jeremy Till, in which Till immediately addresses “fake participation” where architects pretend to involve people while retaining control over the product. Till argues that the only way to prevent design from becoming a “politically required token of democratic involvement” is to be radically committed to giving up control. But architects, planners, and designers have a hard time giving up control because they use expertise as a mode of control. Their professional knowledge is enough to let them know how people want. This reminds me of the adage that people don’t know what they want until you give it to them.

One solution might be relying on professional knowledge to act as guide in participatory design. For instance, instead of using expertise as a tool of power, architects can use professional knowledge to assist participants through the design process. Goodwin’s (1994) notion of “professional vision” highlights the benefit of expertise by showing that the professional has the ability to see nuances of a scene that are invisible to the untrained eye simply because of their expertise and knowledge acquired through experience. Trained designers have a special kind of vision when it comes to solving design problems, and Till acknowledges this by charging designers to use their skill to empower people in “new forms of social constructions” (p.9). According to Till, professionals have an obligation to empower non-professionals - to help users engage in designing and to relinquish control over the process, even though it poses “a real challenge to professional values” (p8).

PARTICIPATORY URBANISM REFRAMES “EXPERT”

In traditional ethnographic practices, an ethnographer spends time conducting something called participant observation which helps the ethnographer understand a cultural group from an insider’s point of view. Design ethnography is no different, and it is something that is necessary if professional designers are going to successfully engage in participatory urbanism.

Ethnography takes as a basic principle that the people are experts on their culture. With design, can we say that users are experts on the needs they experience? It would be interesting to do some discourse analysis to dissect the scene of participatory design settings to see where power-relations and conversational turn-taking establish or regain control in arguments. Do the architects listen, or do they wait to shoot down an idea? When users talk about design issues in their own language, can the professional work in that language or do they have to impose their professional terminology?

Till is one step ahead, because he already sees participatory design as participation of experts, where the “experts” are users, despite the users speaking a different design language than the architect. Serafina Amoroso discusses this notion of expert user (expert-citizen in her terms) in her article Participatory Urbanism: New Learning-scapes in Contemporary Cities when she says that “highly trained architects need the knowledge of the user (as expert-citizen)” and that “knowledge is not a content (of facts, concepts, and theoretical principles) to be transmitted and learnt: it requires a deeper understanding in terms of experience and empathy” (p102). Only the people who use the space have the knowledge of what that space means to them. These user-experts have knowledge that is relevant to the design process and product, and the goal must be to translate between the expert knowledge of the user and the expert knowledge of the architect. Is it all in the framing of the problem?

Clearly this situation smacks of Rittel & Weber’s 1973 notion of “wicked problems in design”, particularly the notions that there is no stopping rule to determine whether the design operation should stop or continue, that solutions are not right or wrong, only good or bad, that every wicked problem can be considered the symptom of another problem, (basically, sets of what archeologist Ian Hodder calls entanglements - networks of dependences and dependencies that bind together the domains of everyday life with the structures that support and enable a way of life to continue). It is the framing of the problem that helps designers and participants identify a potential solution, but designers and participants often think about the problem with entirely different frameworks so aligning those different framings and the expectations they entail is necessary if anything is to move forward.

Even when participant-driven design works and the result is a design that fits the users and the context, that design has a shelf-life until the next set of users come along or the budget changes or environmental conditions shift or the occupancy determines a new set of goals for the space. Design practices that favor participatory urbanism by including participants in the process have to relinquish control in an on-going manner. It is truly a situation in which the designer has to roll with the punches, those punches being shifting needs, shifting populations, shifting goals. Rittel & Weber tell us “there is no definitive formulation of a problem” because the problem is always shifting, and so the answer needs to always be shifting as well. I think we can theoretically accept these ideas as ideals, but practicing them proves more difficult.

PARTICIPATORY URBANISM HITS ONE MOVING TARGET, WHILE CREATING ANOTHER ONE

Part of why a wicked problem is so wicked is that it continually works to undermine the solution. The final characteristic of the wicked problem, that the social planner has no right to be wrong, makes it really hard for the designer to practice the most important skill in participatory design: trust. The drive to control authoritatively starts to undermine any progress toward participation as trust of the participation process gives way to mistrust of the agent/actors engaged in participation.

Going back just a bit, I think this is why Till says “In participation, you have to relinquish that control and become a different kind of professional. You have to acknowledge that your expertise is as good as the expertise of others, but different. However the relinquishing of control is a real challenge to professional values.” [p8]

To have participatory urbanism do we need to embrace a post-disciplinary design practice? Do we need to acknowledge the user as a “professional user” and invite them to the design process both at the site and at the planning table? Who really has user-expertise?

Till goes on to argue for architects to use their forms of social knowledge to empower people to participate in social forms of design. This resonates with what Gonzalo J López says about on expertise and open source urbanism in his chapter Towards a New Urbanism: Emergent Strategies. He says that the role of the expert should change to become an open network of experts where “each component shares its specific input” (p22). This is more than just a specialist-generalist debate because it argues for distribution of expertise across a network. Obviously approaching design in this manner will result in confrontation, but Till warns architects to realize that “participation is a process of confrontation” (p11). Confrontation is an act of negotiation if the parties involved don’t give up prematurely and walk away from the table. Is participatory urbanism about endurance? Is it about tolerance?

PARTICIPATORY URBANISM IS MESSY & CONFUSING, BUT WORTH IT, BECAUSE IT CREATES WHOLENESS

Maybe successful participatory design is about being able to live with ambiguity. Planners and architects don’t deal well with sustained ambiguity and that’s a problem when it comes to participatory design in part because insurance brokers, construction crews, inspectors, and license boards don’t deal well with ambiguity. But living with ambiguity is an essential practice that social designers need to develop because ambiguity pervades in participatory urbanism. Participatory design gives agency to non-formal designers, and that is problematic to controlled design because it doesn’t retain control.

Removal (as we read in Tom Marble’s The Interactionist City) is often painful for the city, and in Luis Eduardo González’s piece Citizen Participation in Chilean Urban Micro-Strategies the “I love my neighborhood” program is one example of the way that people tie their emotions to the places they inhabit because they love those places. Loss is painful in a place that you love, but can participation and user-driven removal turn the feeling of loss into tangible value for a neighborhood?

This past January I participated with a team from the Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative (CUDC) in a submission to Tearing Buildings Down, a design competition held by The Storefront for Art and Architecture. We proposed a participatory design strategy for the removal of C-grade buildings in Cleveland’s Slavic Village neighborhood to create new pathways, viewsheds, and olfactory paths through the neighborhood through a partial carving (a sort of reference to the work of Gordon Matta-Clark). In 2015 a survey of all buildings in Cleveland ranked them as A to F, and the buildings that were ranked as C-grade were marginal and presented a tipping point for Cleveland. We wanted to obtain what Christopher Alexander describes in A New Theory of Urban Design as “wholeness” (1987), a principle of design that obligates new construction to create a “continuous structure of wholes around it”, but instead of applying the rules of wholeness to construction, our proposal applied it to the removal process - to restore wholeness through strategic removal. A central aspect of our proposal was to involve non-formal designers into the process as “removal agents” to help achieve Alexander’s “piecemeal growth” of a “positive urban space” by growing larger wholes in the neighborhood. Removal agents included architects and city departments, but importantly, also residents and industrial corporations, while recognizing the ecological role played by non-traditional design agents like arsonists and scrappers in the process of removal throughout the last hundred years in the neighborhood. Our design was to make use of a diversified and informed and intimately invested agency so that blocks, and then neighborhoods, and then cities could guide their own change.

Creating value through removal provides a ready testbed to develop authentic and meaningful participatory urbanism because removal is tied so tightly to emotional responses of the community (the true user base for a neighborhood), and users are motivated to participate when they have strong feelings about it. That’s called ownership and ownership works at all scales. Going back to Amoroso’s article, it’s worth noting that she points out how the tactical urbanism projects she cites all share a common feature: the absence of authorship because all of the work is co-produced (p106); it is owned by the group, not by an individual.

PARTICIPATORY URBANISM CAN BE INCREMENTAL

López talks about participation on multiple scales, moving from small scale to large scale, to multi-scale, to the collective scale and he argues for participation in appropriate measures along the spectrum. The idea of scaling up the process of participation necessarily pushes it beyond the piecemeal and ad hoc urban decisions of the architect and into the holistic and integrated design process of cities. And it seems to me that participation should be able to scale because the user bases scale and participatory urbanism at it’s core is a user-involved practice. But there is that nagging problem of the shifting needs and populations. In a few years, the user base has moved on and the designed space is inhabited by a different group of users, should they adapt their use to the old space? It gets very sticky very fast. López does not believe the expert should be demised, so he retains a sense of expert-driven design through different scales, while aiming for participation in the execution of the design. How does that play out in tactical urbanism?

The system doesn’t stop participatory urbanism from popping up, and that’s a good thing since tactical urbanism produces smaller scaled interventions that make users aware of the spaces they inhabit toward the goal of enduring long-term change. Amoroso points out (in a quote that I’m reproducing in full), that “Experiments in niche spaces may not constitute a threat to the system of power, in the same way that small scale interventions or micro-urban actions that exploit the gaps in regulations may not challenge property values and the speculative manipulations of urban realm, but, in spite of that, they are capable of activating processes of change and editing urban spaces that are perceived as edges and boundaries, thus influencing the emotions, the behaviours and the psychological well-being of users and inhabitants” (p106).

This ecological approach to participatory urbanism is very much focused on doing what’s best for the user and empowering the user to assist in Alexander’s notion of the “piecemeal growth” of the larger whole. Participatory urbanism is incremental, but at it’s core is holistic - a kind of design strategy that emphasizes part-whole relations and the inter-connectedness of users by prioritizing their voice in the design process.

After reading MONU #23, I come away with the sense that participatory urbanism is an issue that every designer needs to think about, and quickly as we continually move toward post-disciplinary design that increasingly design with citizen-experts at the table. MONU #23 is a good field guide to some of those issues.