5. TRANSCRIPT OF MY TALK AT THE INSTITUTE FOR LAND AND ENVIRONMENTAL ART IN SWITZERLAND

Last week I gave a talk about this project during the Critical Grounds: Art and Politics of Landscape symposium at the Institute for Land and Environmental Art in Switzerland. The talks were recorded for the Institute’s archives, but aren’t available publicly, however, I have the transcript of my talk and wanted to share the talk in a format better suited for a blog post. I’m leaving out a section of the talk where I described influences because I’ve already covered that in another post.

After the talk I took questions while holding the boulder. Unfortunately I did not transcribe the Q & A session.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CF0Bi7AleSs/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Thank you Hanna [Hölling] for that lovely introduction.

And thank you to Johannes [Hedinger] , Hanna [Hölling], and the Institute for inviting me to speak today.

This Stone Wants To Go Home.

Standing at the edge of the canyon or moving up the side of a mountain inspires a moment of geologic awe.

Our bodies help us make sense of enormous spaces… we comprehend the scale of a space relative to the size of our bodies.

The experience of feeling small in a vast space is exhilarating.

But thinking about geologic deep time does not inspire that same sense of exhilaration.

It’s difficult to comprehend a billion years; we use our bodies to make sense out of an enormous space, but when it comes to enormous lengths of time the only frames of reference that are available to us are our lifespan and our notion of generations.

[Alex Grunenfelder for scale]

Things complicate when we talk about planetary change that happens over time.

The hidden complexity of planetary change is extremely difficult to visualize because we don’t live at planetary scale, we live at local scale.

And our physical experience of space is limited to the moment in which we occupy that space.

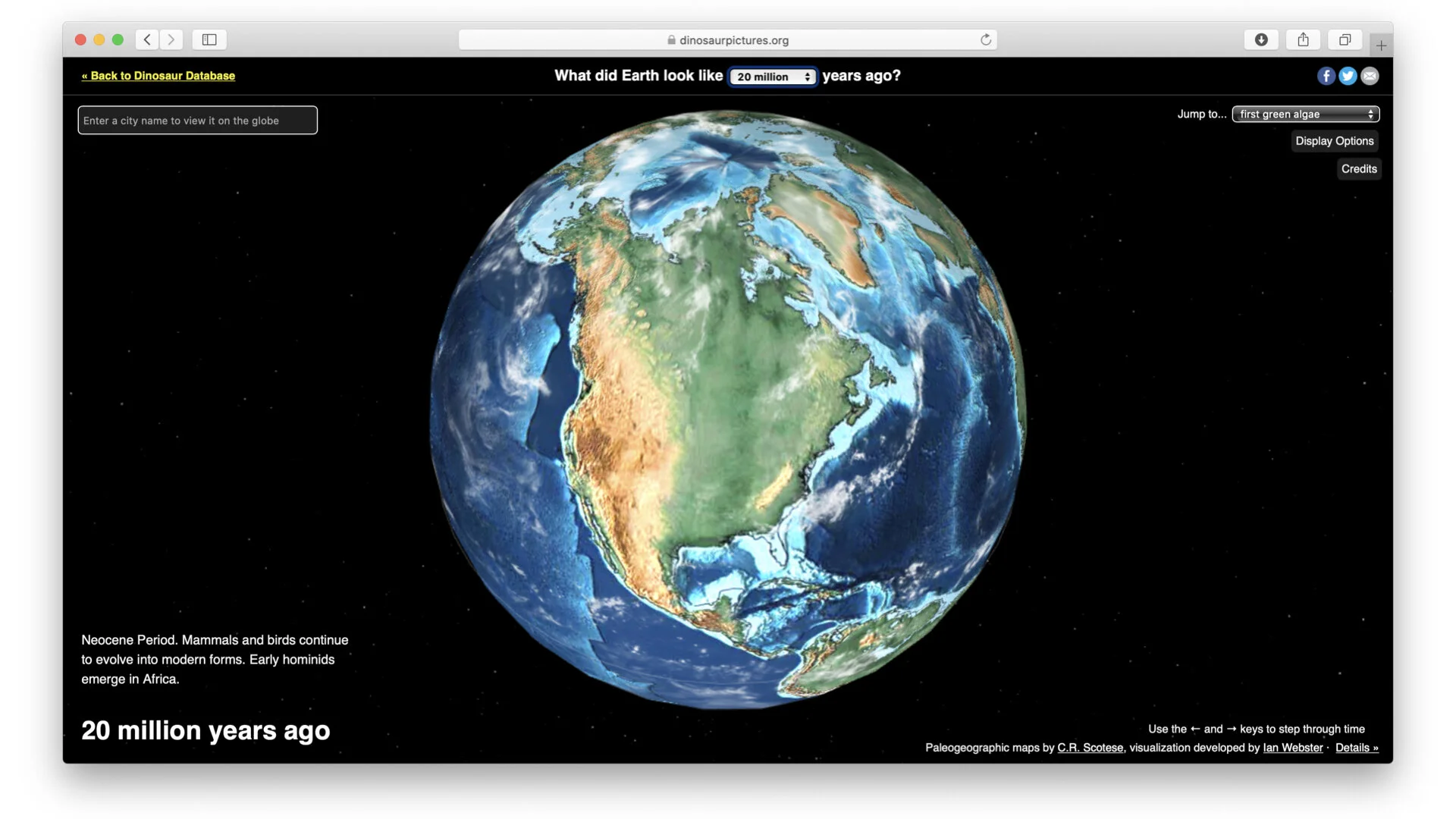

To look back in time we have to build simulations and models.

Here is a model of the planet before the last ice age, and before sea level rose to fill the Hudson Bay in northern Ontario. Before the Laurentian Ice Sheet melted into the Great Lakes which are absent from this image.

In a way, maps become the tools we use to think about the spaces we do not currently find ourselves in, as much as they are tools for locating ourselves in physical space when we use them for navigation.

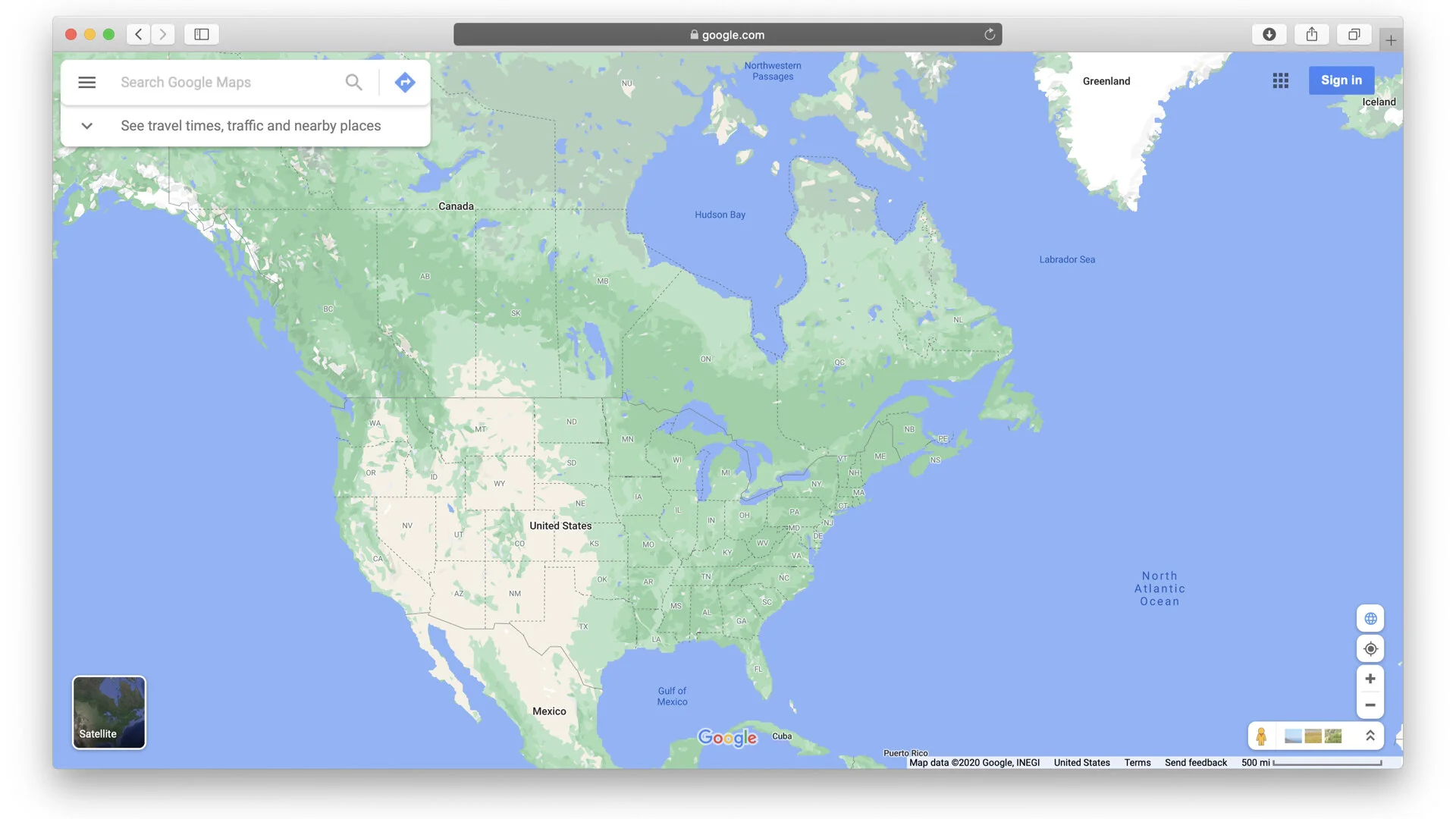

Here we see the Great Lakes and the Hudson Bay have manifested, as well as borders.

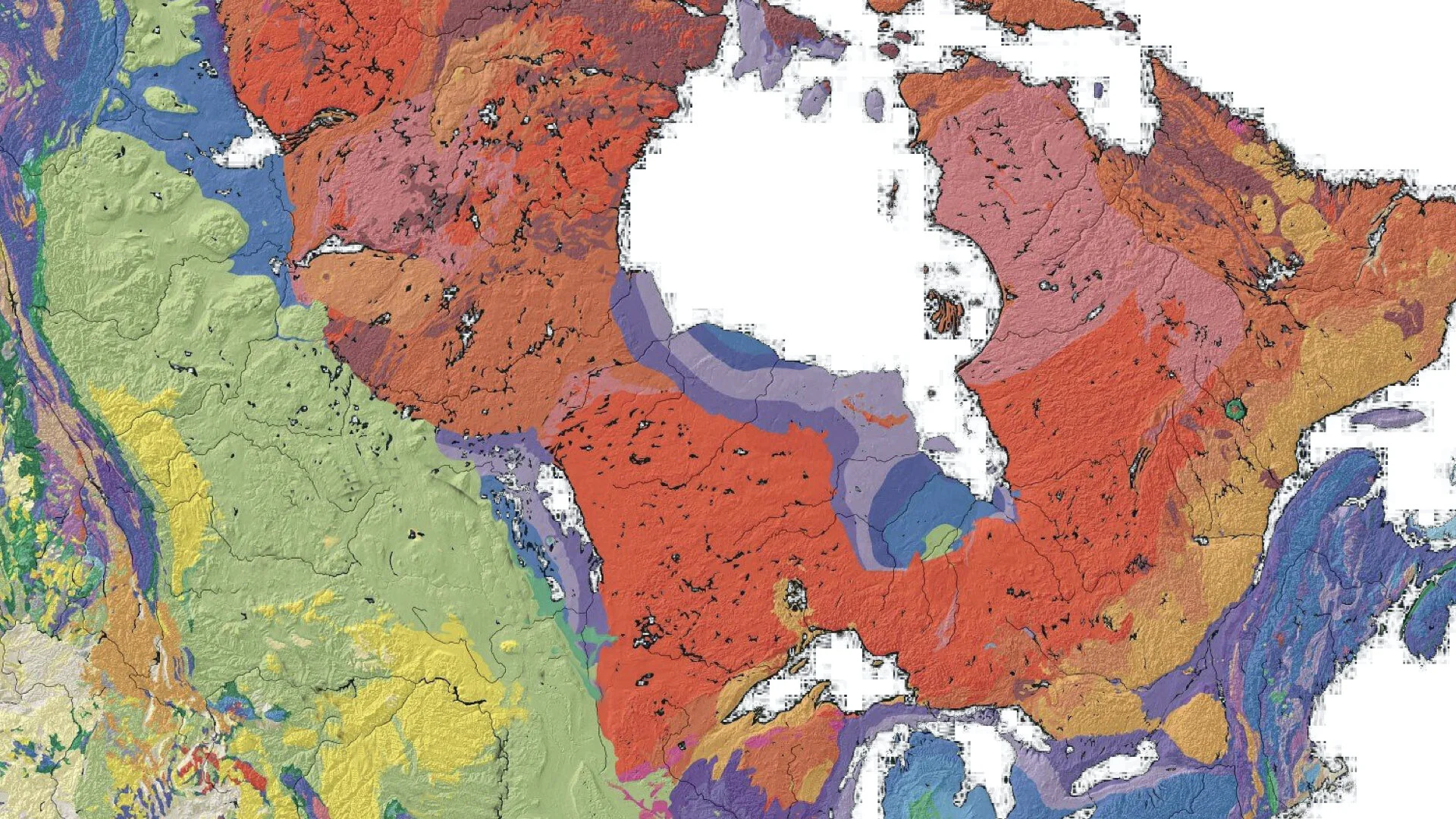

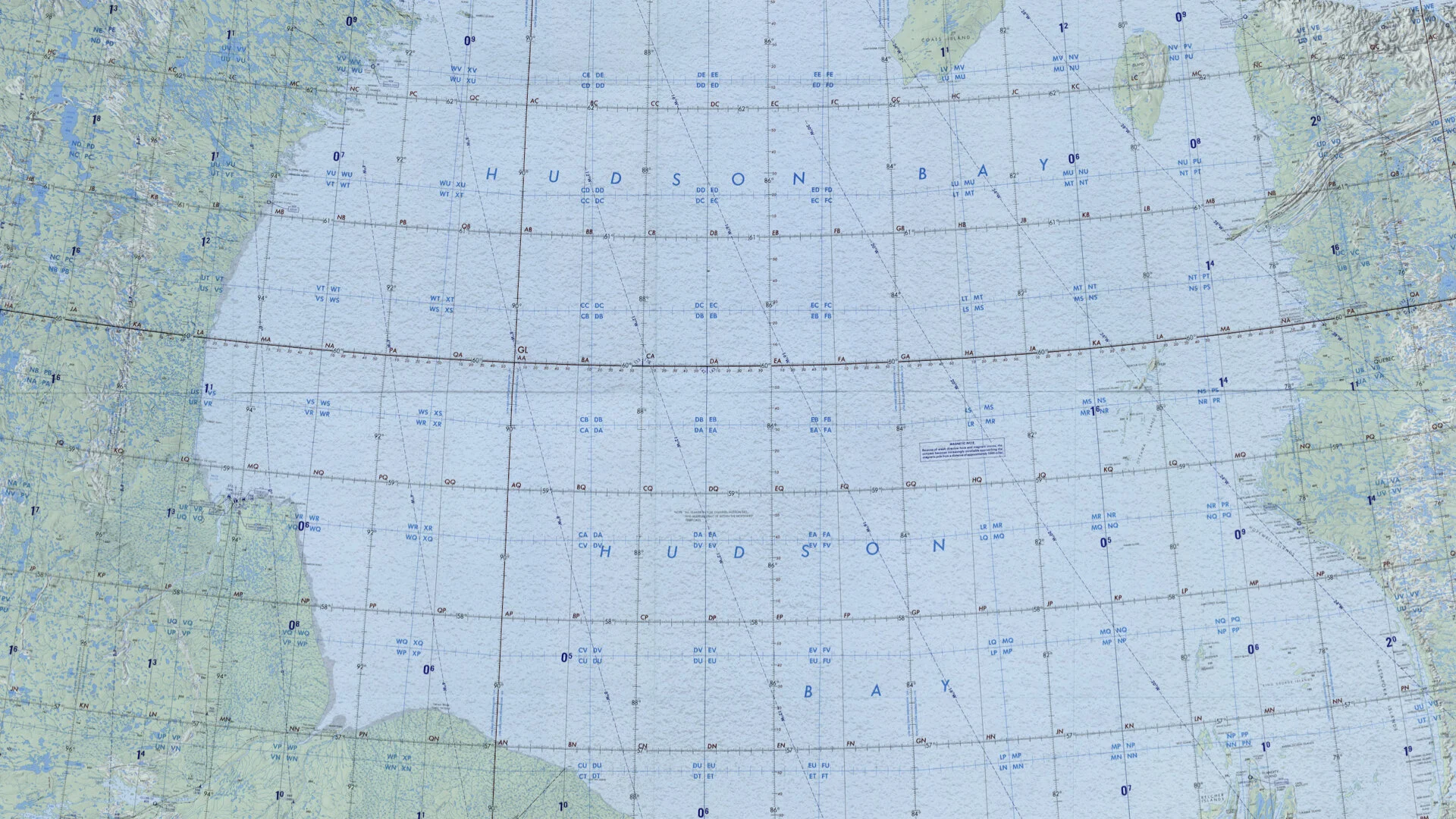

This is a geologic map of the Canadian Shield, one of the oldest rock formations to survive to our present time.

I show this because during the last ice age, continental glaciers broke off and pushed south massive pieces of the Canadian Shield into the Northern United States.

We’re going to talk a lot about these rocks in the slides to follow.

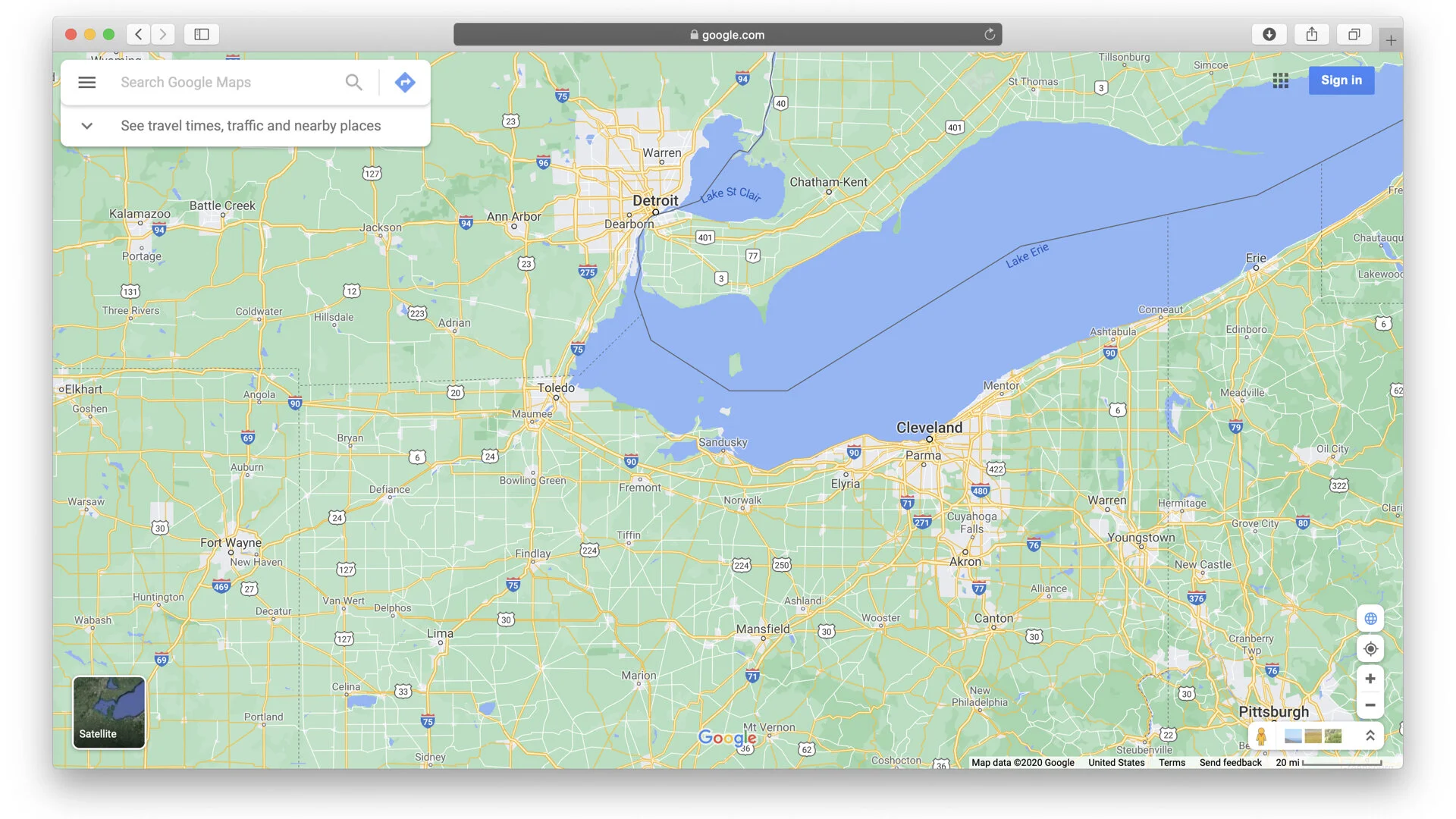

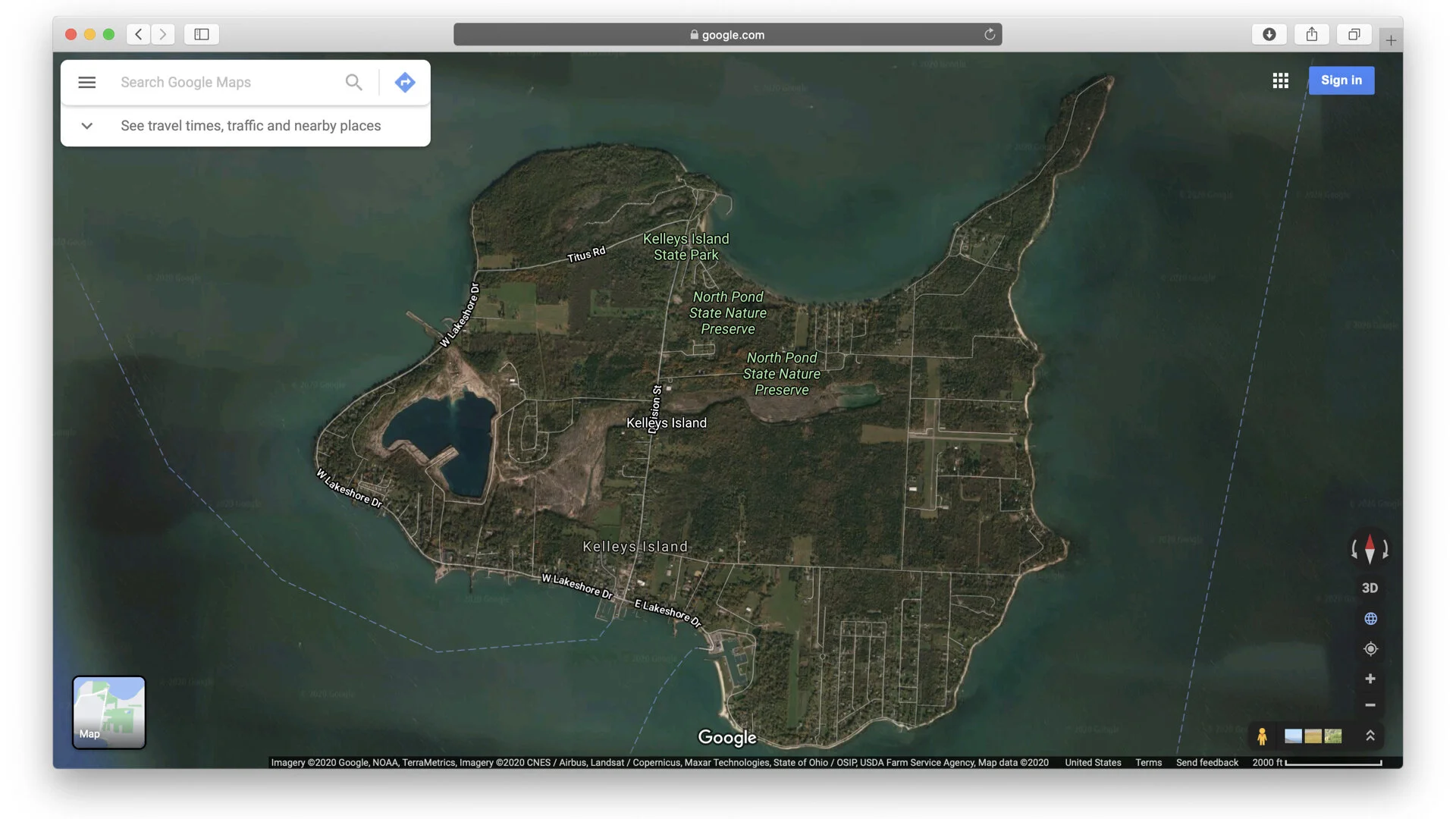

Here is a map of the southernmost Great Lake, it is Lake Erie, and it’s nearly a stone’s throw from where I am standing right now.

On the western end of the lake there is an island called Kelley’s Island, it looks like this:

You can walk around this island in a single day.

It’s a nice chunk of limestone that popped up at the edge of the limestone basin that cups the Great Lakes. It’s Devonian era limestone from a Silurian sea that evaporated 300 million years ago and was subsequently covered with half a kilometer of glacial clay during the last ice age.

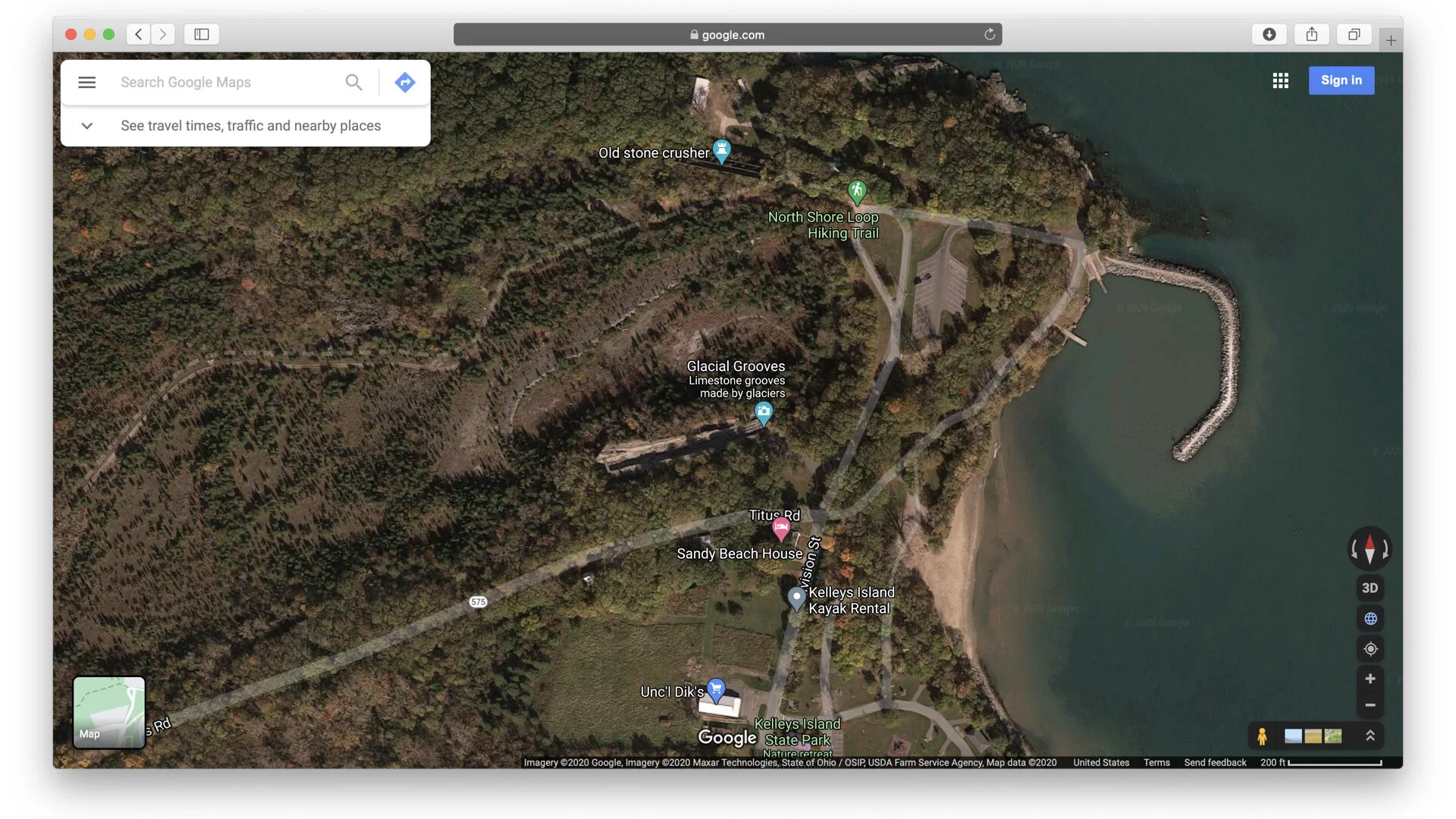

On the North end of Kelley’s Island is a set of grooves carved by Canadian granite glacial erratics under the weight of the 3200 meter thick Laurentian Ice Sheet.

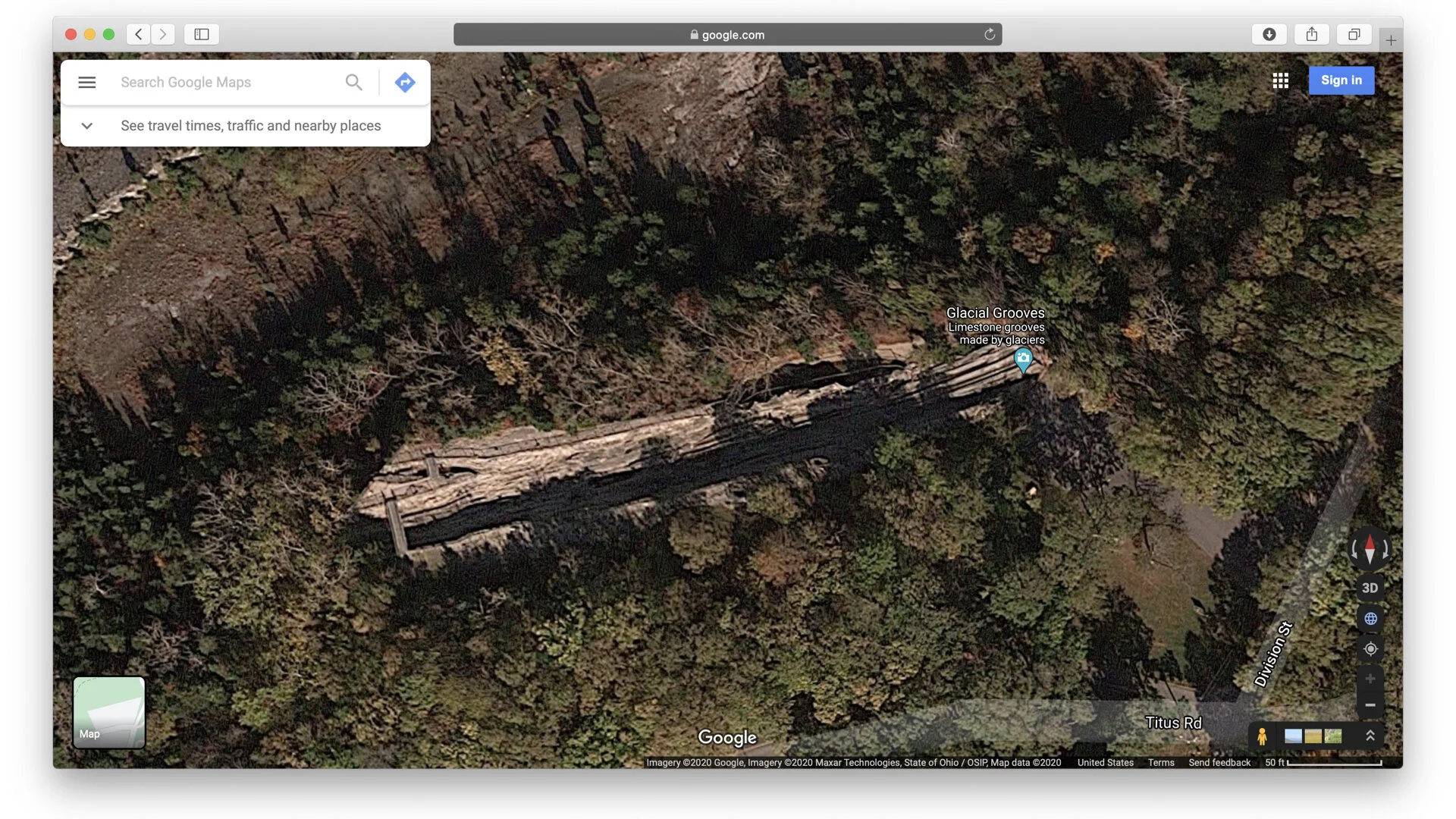

These are massive grooves that remind me a little of Michael Heizer’s Double Negative in scale.

You could park buses in these grooves.

Here’s an image of the fluting and carving from the erratics.

As a side note: In a week I’ll be visiting these grooves again because I’m currently carving a series of Alpenhorns, and inside the bells of these horns I’m carving models of these glacial grooves so that when the horns are sounded, their voices will be shaped by the contours of the grooves.

Here’s a texture image of the grooves. It’s amazing these have lasted until today, Kelley’s Island was once covered in these grooves, this is the last bit that remains.

The entire Great Lakes region is covered with 500 meters of glacial clay, and it’s full of glacial erratics. I’m constantly collecting these from farm fields as they are turned over when soil is tilled each year.

I have shelves and shelves of them in my studio.

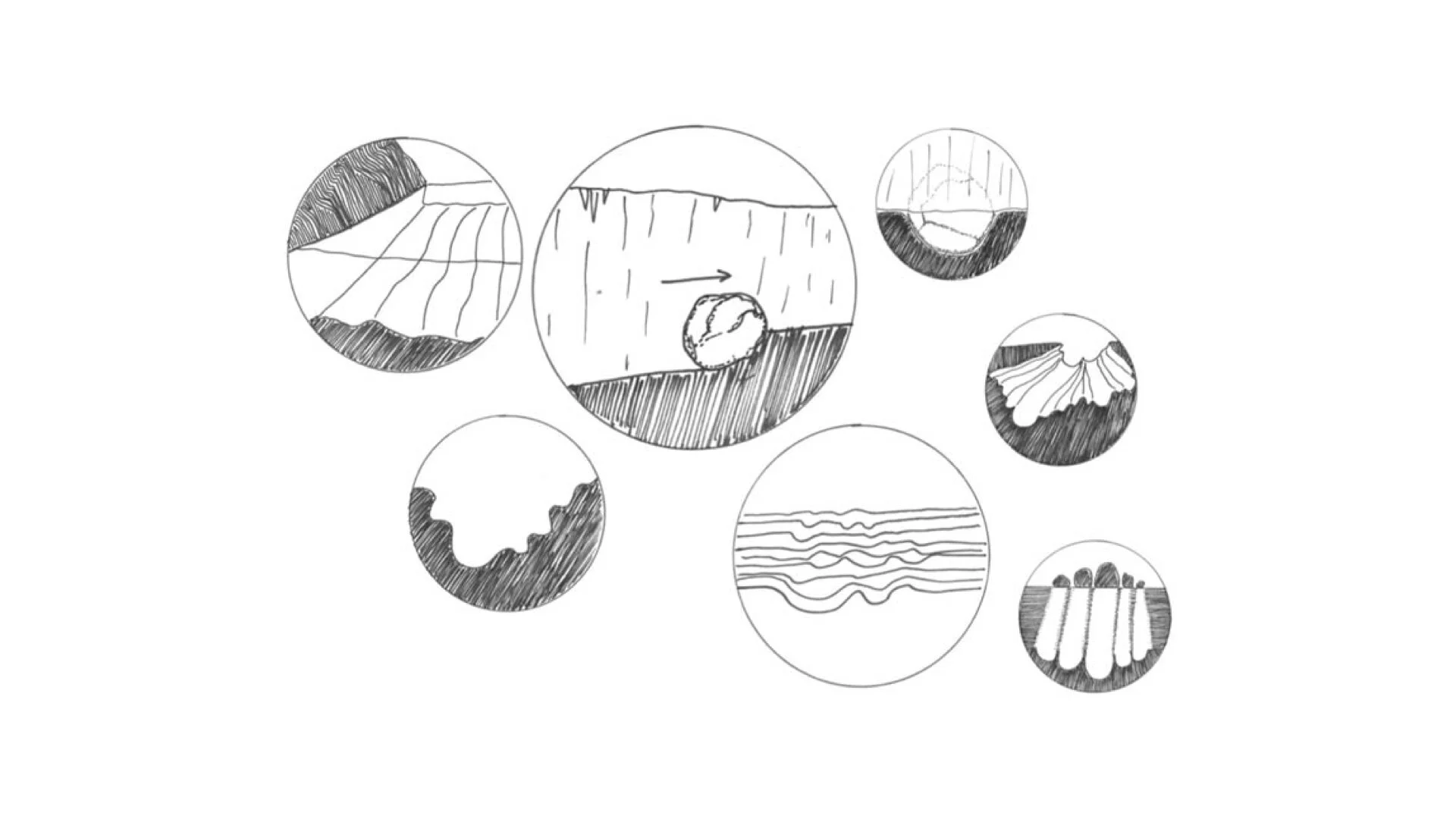

I started thinking about the shape of these grooves and the process involved in producing them. And I wanted to understand it better.

And so I built a hand tool that is essentially a miniature glacier with three tiny granite erratics.

I wanted to empathize with a glacier and experience the agency of the glacier as it carves stone.

SLIDE 14

SLIDE 15

Here is the hand tool on a slab of limestone.

I advance and retreat like a glacier for 20 minutes of continuous motion until the glacier breaks apart, calving and dropping the granite stones on the limestone field.

SLIDE 16

Back to erratics. Here’s a 17kg Canadian Granite Erratic I found in a limestone quarry. I’ve used this as an object to think about timescales, to think about geologic migration, and to build moments of contemplation for viewers to meditate on deep time.

Here is one of those experiences. At the start of a recent solo exhibition about climate change and agriculture, I placed this stone next to an ice box and had participants chill their hands for 30 seconds before touching the stone. The piece is called: Remember for This Stone A Colder Past and you can find it posted (here) on my instagram page @geocog

SLIDE 18

The networked nature of climate change requires us to anchor parts of the problem onto discrete examples that illustrate the larger system.

A plastic straw can collapse an ecosystem, not just in how we discard it, but also in everything it takes to produce and distribute it.

Luxury kitchens are a great place to start to think about landscape.

Here is a reconstructed granite boulder that I made from scraps left over from custom kitchen counter installation.

A granite countertop takes 2 weeks to move from a quarry in China to a retailer in California.

That’s 10,000 kilometers in two weeks time.

A glacier could never move a piece of granite 10,000 kilometers in as fast as 2 weeks.

Hanna [Hölling] talked earlier today about “fashioning potent metaphors of the term landscape in critical grounds”…Here I’m talking about the supply chain as an infrastructural landscape, and one that has surpassed geologic forces in terms of the migration of natural materials.

Supply chains have surpassed geologic forces, not just in terms of accelerated atmospheric carbon from the mechanism of the supply chain, but also in purpose of the supply chain which moves materials from point A to point B with maximum efficiency.

Again, a glacier could never move a piece of granite 10,000 kilometers in as fast as 2 weeks.

I want to think about my role in planetary change, and I also want to collaborate with the natural world.

SLIDE 19

Granite is magma that has cooled slowly at different rates. What we call lava stone is the same magma, just cooled faster at the surface. As granite slowly cools, different minerals precipitate out of the chemical composition of that magma producing crystals, garnets, and other stones.

It’s why countertops look so interesting.

Here I have taken the granite dust from a countertop manufacturer and melted it into magma in my foundry to show how it’s practically the same as lava.

SLIDE 20

Here is another reconstructed granite boulder that I made from tiles I bought at a major retailer who imported them from India.

SLIDE 21

But back to this stone.

One day I was walking in a limestone quarry in Ohio and I came across this granite boulder.

It’s a glacial erratic, and I can be sure, because there is no surface granite in Ohio, and also because the entire region was covered with continental glaciers during the Wisconsin Glacial Episode, glaciers that were 3200 meters thick, glaciers that covered the Great Lakes region with half a kilometer of glacial clay.

This stone moved south from the Canadian Shield into Ohio maybe 1600 kilometers over thousands of years.

That’s a long way for a stone to move, no matter how fast it moves.

When Hanna [Hoelling] talks about rescaling, I want to know what did this rock see? How did the continental glacier experience the North American continent as it carried this stone? What temporalities has this stone experienced?

As I said, I’ve shown this in other exhibitions to help people contemplate deep time, but recently I’ve begun to see it as something more than an object.

Perhaps by reminding this stone of what it felt like to be cold inside a glacier, I had teased the stone, or awakened it. Because Now this stone wants to go home.

In a way this stone is a statement from the last ice age. It is a word pushed south and spoken into the landscape. Left behind for the place to remember. It is an utterance, and it has meaning…semiotically, semantically, and spatially.

While reading the landscape I picked up this meaning, and understood what it meant because I had landscape literacy of the place where I found it. This is a kind of situated knowledge.

SLIDE 22

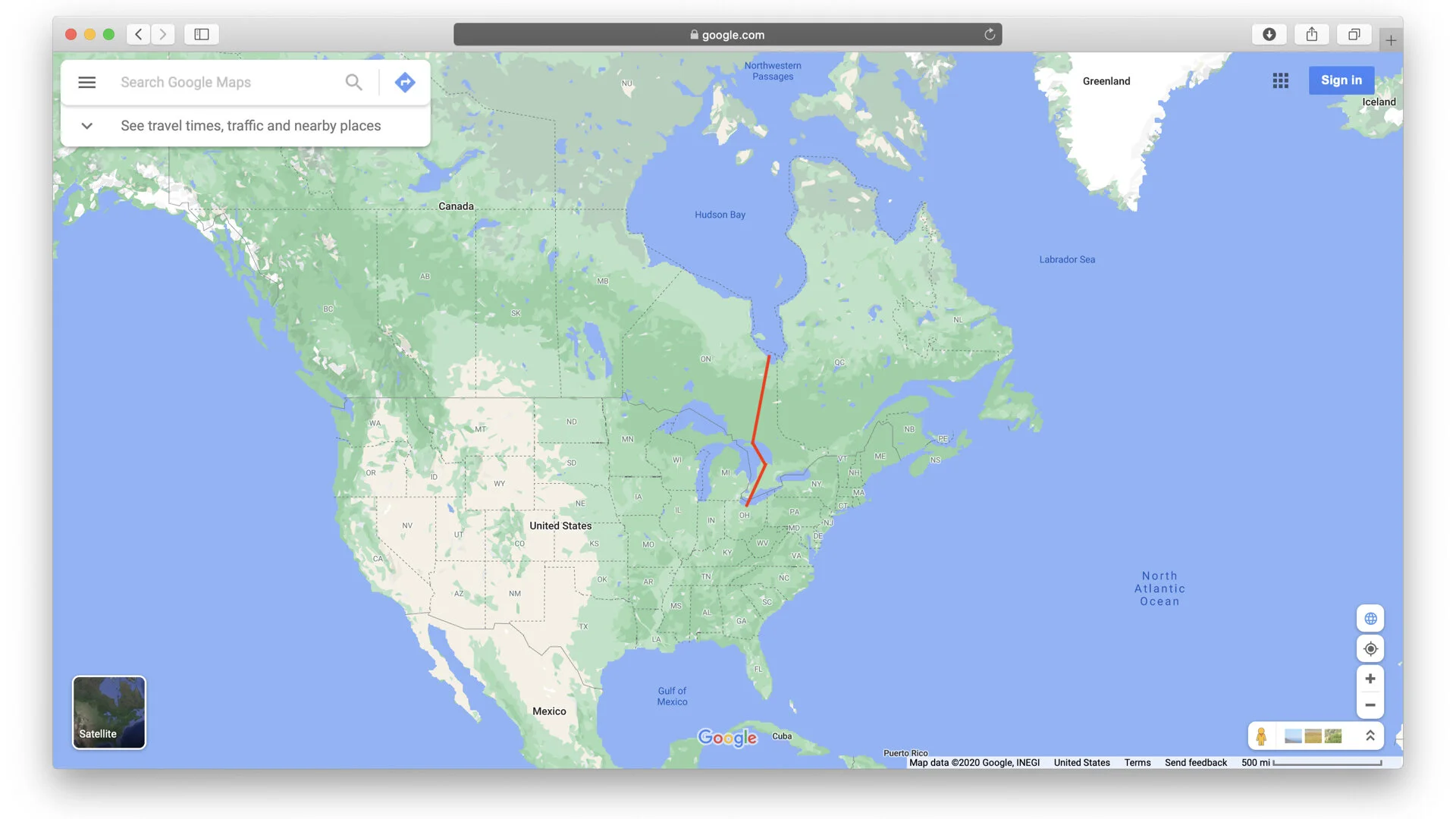

Now some 20,000 years after a glacier dropped this stone in Ohio, I am going to walk north 1600km to throw it into the mouth of the Arctic Ocean at the Hudson Bay, why? so that it is ready for the next ice age of course.

It’s a kind of resetting of the glacial field.

I want to walk because it is the most glacial pace I can take.

I want to develop the same landscape knowledge that this stone developed as it traveled south 20,000 years ago.

This project is also a kind of conversation between the last ice age and the next one. The stone is a message that is being passed back and forth like notes between friends in class. I’m just in the middle, along for the ride.

SLIDE 23

As I said, part of my practice is to empathize with geologic forces, to understand them by replicating their actions at human scale. This stone moved 1600 km over thousands of years, and I will carry, push, and pull this stone (three actions glaciers use to move erratics) in a custom fabricated cart as I move on foot northward to the Hudson Bay over several months, at a rate of ~16km a day.

SLIDE 24

Along the way north, I’ll stop at 160kilometer increments and invite people into a conversation about this stone, land, ownership, climate change, and deep time. It’s not just about fostering “conversation” between two distant ice ages; I’m interested in this being a project that actually gets people talking. And I want people to help welcome this stone as it returns home. A kind of intrepid geologic agent.

This year, on the 15th of September the Arctic Ice reached its second lowest extent in recorded history. Multiyear ice is thinning and melting faster.

Atmospheric Carbon has delayed the next ice age which should be happening 50,000 years from now, but now will not take place until 100,000 years from now, or longer.

But this stone is going to be ready for the next ice age.

SLIDE 25

I’ve never been to the Arctic, but this is what the shore of the Hudson Bay looks like.

This stone can’t wait to get home.

As I’ve planned this project I’ve reflected on some of the art that has influenced me and I want to take a few minutes to talk about these projects because they are the kinds of projects that have helped me rescale my perspective to that of the stone.

NB: Slides 26-33 have been omitted from this post and are discussed in another post.

SLIDE 34

In closing, this is a poster I made for myself a long time ago. It says: Your Experience Of the Earth is Limited by the Human Condition.

I want to suggest an update, that when you situate yourself in the agency of a glacier, or take the viewpoint of an erratic, you can experience new multitudes.